The scientists who eventually get to peer out at the universe with NASA’s powerful new James Webb Space Telescope will be the lucky ones whose research proposals made it through a highly competitive selection process.

But those that didn’t make the cut this time can at least know that they got a fair shot, thanks to lessons learned from another famous NASA observatory.

Webb’s selection process was carefully designed to reduce the effect of unconscious biases or prejudices by forcing decision-makers to focus on the scientific merit of a proposal rather than who submitted it.

“They assess every one of those proposals. They read them. They don’t know who wrote them,” explains Heidi Hammel, an interdisciplinary scientist with the James Webb Space Telescope. “These proposals are evaluated in a dual-anonymous way, so that all you can see is the science.”

This is a recent innovation in doling out observing time on space telescopes. And it’s a change that came about only after years of hard work done by astronomers who were concerned that not everyone who wanted to use the Hubble Space Telescope was getting equal consideration.

A bias emerges in who wins telescope time

Focusing on the science, not the scientists

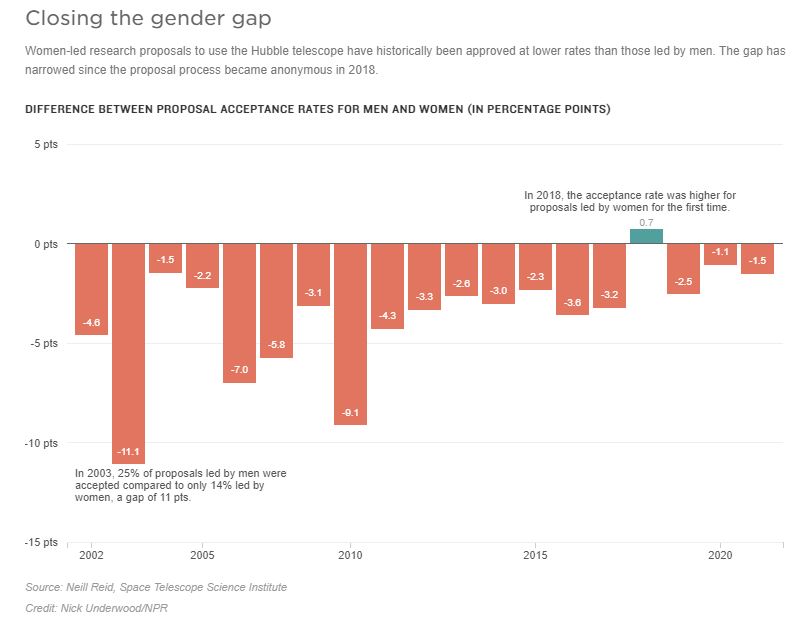

After his study showing a gender discrepancy in acceptance rates for Hubble proposals, Reid and his colleagues tried different solutions. First, instead of having the lead scientist’s name on the front page of a proposal, they tried putting it on the second page. Then, they tried just using initials. Nothing worked.

“Then we got sensible and we said, ‘Let’s actually talk to some experts in social sciences,’ because they can understand this better than we do,” says Reid.

They reached out to Stefanie Johnson of the University of Colorado and her then-student, Jessica Kirk, now at the University of Memphis. The pair sat in on the meetings that evaluated and ranked proposals. And they noticed that a lot of the time, the discussion centered on who had submitted the proposal, rather than scientific considerations.

“There might be a question about it, like, ‘Oh, you know, this seems really good but can they actually do this?'” recalls Johnson. “A lot of times, there’s someone who will speak up in the room and say, ‘I know this person … they will figure it out, because that’s who they are.'”

“There is this evaluation not just of the science and the research, but of the researchers,” adds Kirk.

This means astronomers who were already established and well-known got an extra leg up.

“They were getting a pass,” says Reid. “They had a lower bar, in some ways, to overcome, than the scientists who were coming into the field completely fresh with no track record.”

Johnson and her colleagues recommended making the review process completely blinded and anonymous. Not only would the evaluation committees not get to see any names, all proposals would be required to be written in a way that made it totally impossible to know who the proposal was from.

The gender difference flipped: “I was stunned”

And sticking to the science had a real impact. That year, for the first time ever, the acceptance rate for proposals led by women was higher than the acceptance rate for proposals led by men. The gender difference had flipped.

Data from the last few years suggests that this process continues to help close the gap between men and women in acceptance rates for Hubble proposals, and it may have improved fairness in other ways, too.

What other biases could affect telescope users?

Still, anonymizing everything doesn’t solve all the problems in making sure everyone has equal access, says Johnson, who notes that unconscious bias can affect who in astronomy gets advantages such as mentors and job opportunities.

“It’s not perfect. It doesn’t wipe out systemic bias, and I don’t know of the impact that the dual-anonymization has in terms of creating greater racial equity,” she says. “But it did seem to lift some of the gender bias.”

Leave A Comment