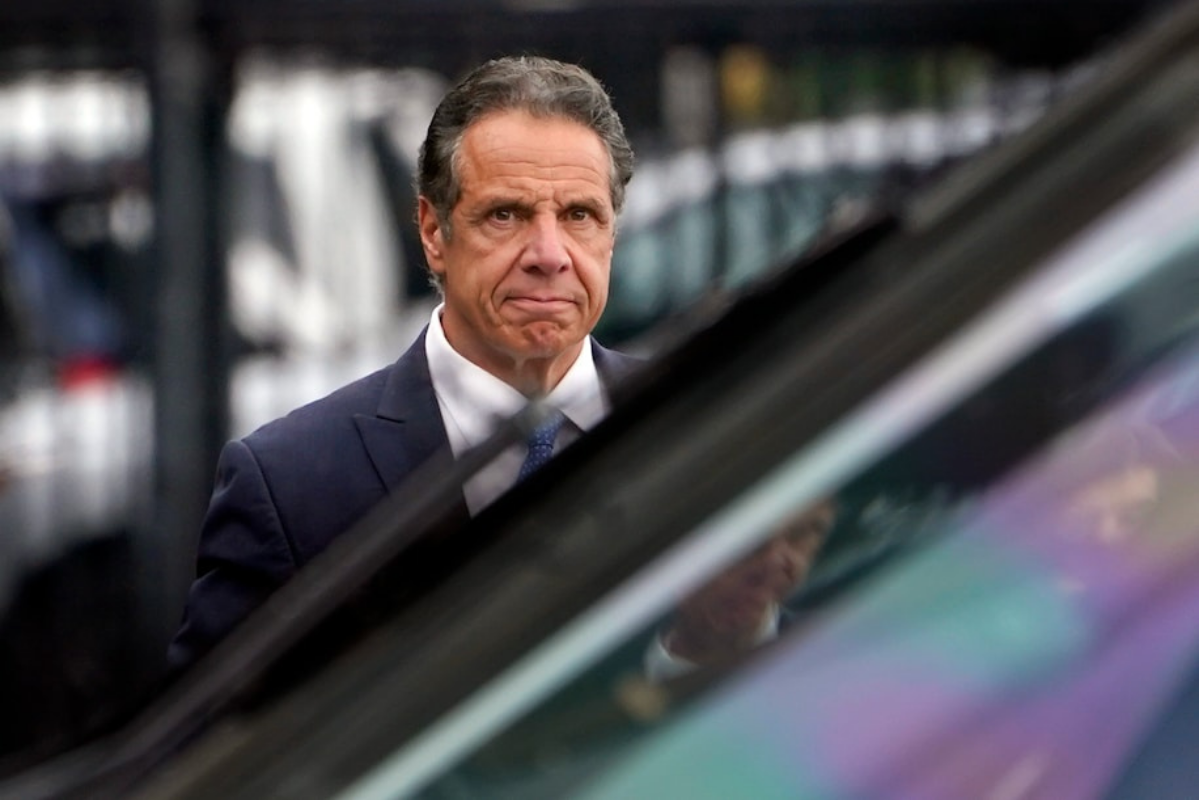

New York Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo was cupping the breast and grabbing the buttocks of subordinates not 10 or 20 years ago, according to the damning state attorney general’s report, but in 2019 and 2020.

The fact that men of a certain age had supposedly learned something about propriety and power dynamics didn’t stop Cuomo from allegedly kissing his executive assistant on the lips.

It’s clear that #MeToo raised awareness about the pervasiveness of sexual misconduct and helped victims better understand their rights and options for holding harassers and abusers accountable. Less clear is the extent to which the movement has curbed bad behavior.

Experts who spend their days thinking about these issues say they’re not overly optimistic that the instances of inappropriate conduct — and the power dynamics that enable them — have changed much since 2018.

“The most egregious forms of sexual harassment have declined,” says Stefanie Johnson, a management professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder’s Leeds School of Business, who has studied the impact of the #MeToo movement on women in the workplace. Her research found that a significantly smaller percentage of women experienced sexual coercion or unwanted sexual attention at the office in 2018 than in 2016.

“If you’re talking about, like, ‘I demand that you have sex with me or you’re fired,’ I think that is less frequent,” she says.

But Johnson’s research also showed that over the same period there was a sharp rise in what she calls “gender harassment” — treatment that “may include things like a supervisor or co-worker making sexist remarks, telling inappropriate stories, or displaying sexist material” — which may have come as a backlash to the #MeToo movement. “Someone might say, ‘Hey that’s a nice suit. Oh, am I allowed to say that? Or are you going to sue me for sexual harassment?” Johnson says. “It’s just as bad as sexual harassment in terms of its impact on women. It’s just not necessarily sexual in nature.”

Leave A Comment